Crayfish conservation: a battle against microbes

People think I’m mad when I say my favourite animals are crayfish. It certainly wasn’t love at first sight, if anything I was afraid of the claws. However, I had accepted a masters with the crayfish so I had to learn how to handle them. The more I watched and lifted them, the more I started to love them. They have a funny waddle when they walk on land, a cool backwards swimming motion in water and they can be affectionate when I stroked the top of their body. Best of all, I’m one of the few to have worked with the endangered white-clawed crayfish!

The crayfish plague

While it may seem unusual to start a microbiology blog with a crayfish, this species endangerment is partly caused by a microbe. They are affected by a fungi-like organism (an oomycete) called Aphanomyces astaci. The white-clawed crayfish has no immunity to this disease and so they will die if they contract it (although there is a population of white-clawed crayfish in Spain that is believed to be immune to the plague, but this requires confirmation). The disease is primarily carried by non-native crayfish such as the signal crayfish which can be immune to the plague. The plague can also be carried on fishing gear but this results in more isolated, single kill events if the non-native crayfish carriers are not present.

The plague is caused by five different genotypes of A. astaci which can infect many crayfish species. When the oomycete produces spores, they are attracted to the chitin that makes up the crayfish’s body and embed themselves ready for growth. The spore then grows producing mycelium (root-like structures) which reach the nerve cord of the crayfish leading to its untimely demise. Upon the death of its host, the oomycete bursts the crayfish’s body open to release its spores and restart the cycle. To make matters worse, the oomycete causing the plague – like many pathogens – evolves with time. This means that we cannot eradicate it and it prevents our crayfish from developing immunity.

Is the battle over?

What can we do if we don’t want our crayfish to join the dinosaurs? Well a number of facilities and universities around the UK and Ireland have set up facilities to breed crayfish. These behave like many zoos with conservation aiming to increase their numbers and to educate. After all, if we do not know about our crayfish, how are we meant to save them?

The battle continues…

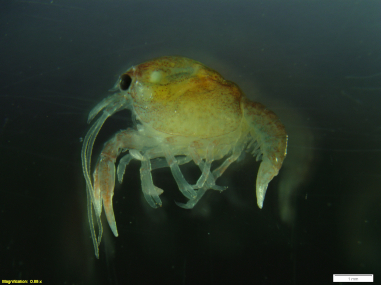

If we want to safeguard their numbers, the first thing we must do is get them to breed (cue the music and turn down the lights). Sound simple enough? However, once they have eggs, the next battle begins: a battle against egg munching fungi. A crayfish mothers keeps the eggs under the tail for the whole incubation (and for around two weeks after they hatch). She folds her tail in around them to keep them nice and safe (particularly from other crayfish), not forgetting to occasionally open and close her tail repeatedly to bring fresh, clean water to her little eggs. But each pass of water brings new microorganisms which could infect her developing eggs – particularly fungi. Crayfish breeders fear fungi, a fear rooted in the basic biology of what fungi do: create spores or mycelium to spread from one egg to another to another. Fungi can and do cause the total loss of the mother’s eggs. A nightmare for species conservationists!

Victory at last!

Thankfully, nature has a solution. The crayfish mothers are clever little critters and they tend to their eggs, removing dead ones with a small claw-like structure at the end of each leg. This ideally stops the spread of natural fungi from one egg to the next. I’m still amazed at how they know which eggs are dead, they do change colour, but the clever mother has usually removed the egg before the colour change, which is when I know it has died. Crayfish breeders have also developed their own methods for preventing fungal infections where we remove her eggs and incubate them artificially, occasionally flushing them in salt to kill fungal spores. This does work, but to quote a popular phrase, I still think “mother knows best”.

Prevention is better than cure

But of course, this is only an attempt to improve a dire situation, the best option would be to disinfect fishing gear before using it in other rivers and more importantly, stop the introduction of non-native organisms (they are escape artists and are known to walk over land to get around obstacles in streams or to move between water bodies). Only with these measures do we have a chance of fighting the crayfish plague. The fight against fungi on crayfish eggs will continue of course, we cannot stop natural fungi and we would be wrong to eradicate these microorganisms which are vital for nutrient recycling. I just long for a day when reports cease on plague-killed crayfish bodies washing up on the edge of rivers and lakes, resembling a battlefield caused by an unwinnable war with microbes.

Alli Cartwright

ECS Communications Officer