Mental health: mind over matter or mind over microbes?

At the moment, everywhere I turn I keep hearing the term ‘mental health’. Recently one of my fellow Duke of Edinburgh Award Leaders was discussing how hill walking’s very positive for mental health. He had read an article about a man who walked through the Pyrenees from France to North Spain. The journey took 5 weeks, but his anxiety was cured by the end of his 1st week.

There is no escaping the complexity of mental health but more recently the human microbiome has been linked to our mental health. With this in mind, I had to ask: how do our microbes affect our mental wellbeing?

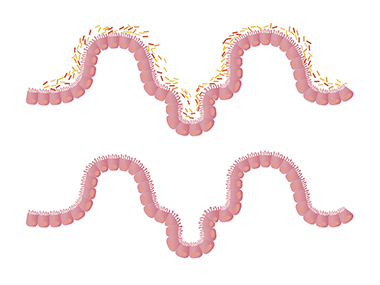

Before I begin, I need to explain that relatively little information has been confirmed in humans with most studies focusing on germ free mice delivered by c-section and kept in sterile environments to minimise their microbiota. Currently, research seems to indicate the gut microbiome is the main microbial contributor affecting the brain. The gut microbiota is mainly bacteria, but fungi, viruses, bacteriophages, archaea and protozoa are also present [1]. As microbes help us digest food, molecules are produced including hormones, immune molecules and specialised metabolites [2]. These molecules can then communicate with the brain via the vagus nerve and affect our behaviour and brain development [1].

Microbial control of our behaviour

One behaviour affected by the gut microbiome is response to stress. Germ free mice exhibit a higher stress response when confined in a tube compared to normal mice [3]. However, this difference disappears when germ-free mice are given the gut-dwelling bacteria Bifidobacterium infantis [3]. B. infiantis promotes the synthesis of kynurenine which links into the production of serotonin through tryptophan metabolism [1]. As serotonin is the ‘happy’ neurotransmitter, any production of this chemical will dampen a stress response thus making the mouse happier even in confinement. In addition to stress, serotonin can also act as an antidepressant further promoting good mental health [2].

If germ-free mice have an exaggerated response to stress due to an absence of a gut microbiome, it therefore, seems logical to assume that a reduced human microbiota could also create an exaggerated response to stress. Could this explain why some people handle stress better than others?

Microbial control of our brain development

If microbes affect our brains as adults, can they affect the developing brain of an infant? When pregnant mice were given an immunostimulant so they had young which exhibited autism like behaviour, the gut microbiota were different [3]. The infant mice had higher abundances of the gut bacteria classes Clostrida and Bacteriodia thus implying that autism spectrum disorders can be linked to gut microbiota [3]. Again, though, it is unclear whether the microbes affect the brain or vice versa. Regardless of the direction of the effect, this connection is associated with early development whereby the microbiota is important for brain development [1]. Additionally, the gut microbes are also important for the development of memories and spatial awareness, vital in social animals throughout their lives [1]. Thus, a lack of microbes in an infant can cause long lasting impact on their brain.

Enhancing the gut – brain link for mental health

If gut microbes are linked to mental health is it possible to enhance our mental wellbeing through diet? The link between the gut microbiome and the brain is complex due to the shear abundance of microbial diversity. However, this is further complicated as the microbiota is not constant. One mechanism which drives gut microbiota diversity is diet.

Due to the importance of mental health, the contribution of diet and gut microbiota to the brain has become a focus for research. The EU even funded the project MyNewGut to better understand the role of the gut microbiome in diet and behavioural disorders including the role of gut microbiome on the development and function of the brain [4]. The project ran for 5 years and cost just over €13 million. By the end of the project, they had sufficient evidence to link the gut microbiome and diet to mental health. They found diets high in fibre and poly-unsaturated fats promoted healthier gut microbiomes thus improving metal health when compared to diets with high protein or high saturated fats [4]. Similarly, in mice high fat diets disrupt explorative behaviour due to the associated microbiota [5].

Having a healthy diet can ultimately improve mental health, but there is also potential to use probiotic, prebiotics or faecal microbiota transplants to alter the gut microbiota in humans to benefit mental health [5]. Tests in mice showed faecal microbiota transplants from a ‘brave’ mouse could be used to make a ‘shy’ mouse more daring [2]. However, research is still needed into what constitutes a healthy gut for mental wellbeing in humans before faecal microbiota transplants can be used to improve mental health.

As the human microbiota becomes increasingly important for mental health, I feel we need to readdress the ‘mind, body and soul’ aspects for ‘mind, body, soul and microbiome’. Hopefully if we look after our microbes, they will reward us by looking after our mental wellbeing. However, due to the complexity at present for linking microbial affects with changes in our brain, I think I may stick to hill walking for my mental wellbeing.

Alli Cartwright

SfAM ECS Communications Officer

Further reading

[1] Diana TG, Stilling RM, Stanton C, Cryan JF (2015) Collective unconscious: how gut microbes shape human behaviour. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 63: 1-9

[2] Smith PA (2015) Brain, meet gut. Nature, 526: 312-314

[3] Schmidt C. (2015) Mental Health: Thinking from the Gut. Scientific American 312: 97-100

[4] CORDIS EU (2019) Microbiome influence on energy balance and brain development-function put into action to tackle diet-related diseases and behaviour [Online]. Available from: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/111044/reporting/en

[5] Bruce-Keller A, Salbaum M, Berthoud H-R (2018). Harnessing gut microbes for mental health: getting from here to there. Biological Psychiatry 83: 214-223